joodse asielwoekeraar bedankt engeland

In 1938 Alex Langsam and his parents fled Austria for Britain because of the nazi's treatment of Jews.

Interesting context: In 1938 Alex Langsam and his parents fled Austria for Britain because of the nazi’s treatment of Jews. Langsam, now the founder and CEO of Britannia Hotels, thanks the Brits by lobbying for mass migration and makes millions every month renting out his hotels to the Home Office for asylum seekers. bron: Dries van Langenhove x/twitter https://x.com/DVanLangenhove/status/1950204589711433761

Rosa Silverman: The Cheshire ‘asylum king’ worth £400m making a fortune from migrant hotels

Alex Langsam’s hotel empire – crowned the worst in the UK – has been attracting the ire of protestors. But the man himself is highly private

28 July 2025 4:41pm BST

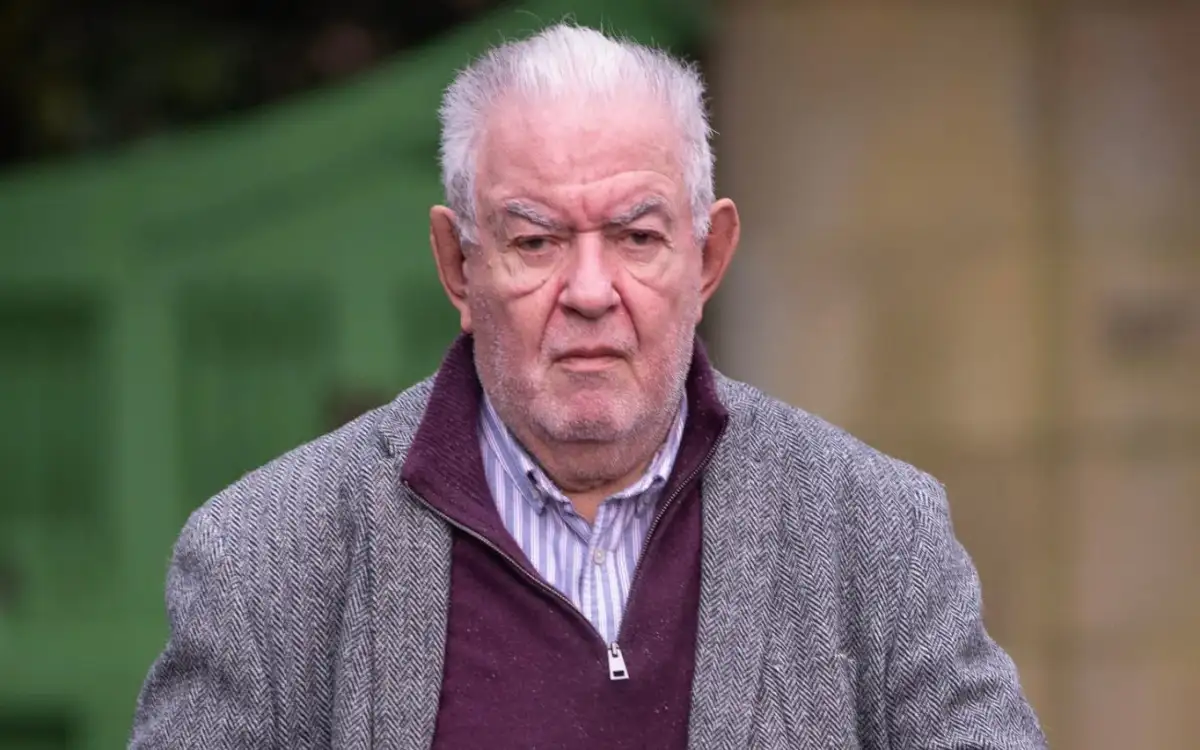

Britannia Hotels chief executive Alex Langsam

Alex Langsam founded the Britannia Hotels chain nearly 40 years ago and remains its chief executive to this day Credit: Andy Stenning/Mirrorpix

For more than a decade, Britannia Hotels earned a dubious distinction. In annual surveys by consumer group Which?, it repeatedly emerged as the UK’s worst hotel chain. In 2023, it achieved this honour for the 11th year running, with complaints ranging from cleanliness and room quality to customer service issues.

Yet the man behind the business hasn’t done too badly. Alex Langsam, who founded the chain nearly 40 years ago and remains its chief executive to this day, was estimated to be worth £401m in this year’s Sunday Times Rich List.

The 87-year-old’s wealth has been bolstered in recent years by the Government’s use of his hotels to accommodate asylum seekers via lucrative taxpayer-funded contracts. In fact, his empire of more than 60 sites has become so well-known as a go-to chain for migrant accommodation that Langsam himself has been dubbed the “asylum king”.

The Britannia International Hotel in London’s Canary Wharf district is expected to become the latest in the group to host migrants.

Britannia International Hotel, Canary Wharf

The Britannia International Hotel in London’s Canary Wharf is expected to become the latest in the group to host migrants Credit: Isabel Infantes/Reuters

A ring of steel has been erected around the site, which has been commissioned by the Home Office as contingency accommodation (at a rate of £81 per room, per night) for small boat arrivals – attracting the ire of protesters.

Protesters outside the Britannia International Hotel in Canary Wharf, where asylum seekers are planned to be housed

Protesters last week outside the Britannia International Hotel in Canary Wharf, where asylum seekers are planned to be housed Credit: James Manning/PA

For all the attention on the hotel of late, Langsam himself, a self-made tycoon whose business spans the country, appears to remain a highly private and somewhat enigmatic figure.

Most of those who live near his sprawling 10-bedroom stone mansion in a village in Greater Manchester seemed unfamiliar with their neighbour when The Telegraph visited last week.

“There are a lot of business people around here and mostly they keep themselves to themselves…. people are very private,” one neighbour commented.

The hotelier’s property (reported to be worth £3.4m) sits on a vast plot surrounded by high brick walls on one side and a long, high hedge on another. A member of staff at his nearby business headquarters said he was currently out of the country.

Bowdon Croft, Altrincham

A high hedge surrounds Bowdon Croft, Altrincham, listed on Companies House as the correspondence address of Alex Langsam Credit: Asadour Guzelian

Indeed, a 2012 court judgment shows that he obtained confirmation from the Inland Revenue in 1999 that he was not domiciled in the UK for tax purposes, “on the basis that he had maintained his domicile of dependence in Austria due to his father’s domicile there”.

Langsam is reportedly unmarried, and work is said to dominate his life.

But competitors with decades of experience in the hospitality industry say they have never met him, and don’t know anyone who has. Indeed, insiders say Langsam’s company has a reputation for not engaging with correspondence from outsiders – be they politicians or property developers – keen to liaise with the company or make offers for its assets.

Fleeing Nazi persecution

He appears to have only ever given one interview to a major newspaper. (The Telegraph’s own approach to Britannia Hotels for comment went unanswered, as is reportedly the norm.) Speaking to The Guardian in 2011, Langsam addressed the fact he and his parents were once refugees themselves, with the family having fled to Britain from the Nazis.

Hitler’s Germany had annexed Austria some three months before Langsam’s birth, and the family took the last train out of Vienna, leaving behind their property and business interests. They would “probably have gone to the gas chambers” had they not been welcomed in the UK, Langsam told The Guardian.

The family were reportedly interned on the Isle of Man, in common with many other refugees fleeing the Nazis, but later ended up in Hove on the Sussex coast.

Those said to be close to Langsam talk of an “entirely self-made, incredibly hardworking” individual. “I suspect the fact that so many of his family were murdered in the Holocaust continues to motivate him to this day,” an unnamed source, speaking on the grounds of strict anonymity, told Unherd last year. “Yes, he has been criticised for providing accommodation for migrants but this was after all at the specific request of our government. They have to live somewhere.”

Those said to be close to Langsam talk of an ‘entirely self-made, incredibly hardworking’ individual

Those said to be close to Langsam talk of an ‘entirely self-made, incredibly hardworking’ individual Credit: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Perhaps unsurprisingly, others take a somewhat dimmer view. Critics have accused Langsam and his company of “raking in as much money as they can from whatever source”, including by cashing in on the illegal migration crisis – which has seen the cost of housing migrants and asylum seekers soar to £4m a day as Channel crossings continue unabated.

As a young man, Langsam studied economics at Aberystwyth University in Wales, joking later that it was the only institution that would allow him to do so after he failed his O-level in maths. He reportedly worked as an estate agent before becoming a property developer and enjoying success with various projects in Manchester.

In 1976, he bought the 100-bedroom Country House Hotel in the south of the city and founded Britannia Hotels. Then, in 1982, he opened his second hotel, having bought and developed a council-owned derelict listed building in central Manchester the previous year.

These were the first two building blocks in what was to become a nationwide hospitality empire. It was from here that he gradually bought and developed more buildings, including historic ones, adding hotels in Liverpool, Manchester, Warwickshire, Stockport, Birmingham, London, Cheshire, Leeds and elsewhere to his expanding portfolio.

There were shouts of ‘Back in your rubber dinghies’ outside the Britannia Hotel in the Seacroft area of Leeds

There were shouts of ‘Back in your rubber dinghies’ outside the Britannia Hotel in the Seacroft area of Leeds

In 2011, the Britannia group bought Pontins from administrators for an estimated £20m. At the time, the holiday camp company operated five parks across Britain and, according to Langsam then, represented “an important part of our shared heritage”.

He promised to provide “considerable investment” and to safeguard the jobs of Pontins’ 850 employees, saying his firm was delighted to be able to “rescue” a “great British institution”.

Langsam added that Britannia had a track record of adopting “neglected properties” and making “the necessary investment to restore them to their former glory”.

‘It’s just been left to go to ruin’

But whether the “necessary investment” has truly been made seems a matter for debate.

In Blackpool, where Britannia’s seafront Metropole Hotel has accommodated asylum seekers since 2021, Labour MP Chris Webb would beg to differ.

“I’ve had concerns about the hotel for a number of years, even before it was an asylum location,” he says. “It’s been an iconic hotel for years but has had a lack of investment, and then it’s been turned into an asylum hotel and… just been left to go to ruin.”

He claims there have been problems of “damp, mould, water coming through the carpet”, and that it isn’t suitable for asylum seekers.

“We’ve seen 520 people in there at times, predominantly families and young people,” he says. “There aren’t suitable facilities in there for young people… [and] it adds a lot of strain to local services.”

He has tried to raise his concerns with the hotel but describes the response as “disappointing”. He has just been put through to Serco, a private company contracted by the Government to provide migrant accommodation (and which oversees operations at the Metropole), he says.

“It’s been difficult to speak to Britannia on this,” Webb adds. Serco has previously denied the hotel had any issues with either sewage or drainage.

Neglect and investment concerns

He is not the only MP who has found it a challenge to communicate with Britannia. Last year, then-Conservative MPs Dr James Davies, Sally-Ann Hart and Damien Moore called for an inquiry into its practices after Pontins sites in their constituencies were suddenly shut down. They too raised concerns about neglect of the sites and a lack of investment.

“Pontins is located in the ward I represented when I was a county councillor in my home town of Prestatyn, North Wales. It was a frequent cause for concern because they invested no money in it and there were persistent complaints from people who visited it,” says Dr Davies, who previously served as parliamentary under-secretary of state in the Wales Office.

“The company never responded to anything that I sent their way. As an MP I tried again and still had no replies.”

The company announced it was shutting the Prestatyn Sands branch of Pontins, as well as the Camber Sands branch in East Sussex, with immediate effect, not long before Christmas 2023.

In October last year, it was reported that Britannia was planning to reopen a holiday park on the Prestatyn site as soon as possible. But Dr Davies says it still remains empty and is “gradually falling into greater disrepair”.

He talks of a “general sense of decline and lack of investment” in the Pontins sites “but also [in] all [Britannia’s] hotels as well – and a feeling they were impacting on the hospitality sector in the country as a whole”.

Dr Davies attempted to contact the company about its plans after the closure of Pontins’ Prestatyn Sands site but “was met with silence”, he says.

He highlights the discrepancy between the company being routinely accused of failing to adequately maintain their estates – and in some cases letting them fall into disrepair – while “raking in” money from “asylum accommodation”. “They were relying on government funds to bankroll their business model,” Dr Davies alleges.

The Home Office, meanwhile, stresses it is bringing the situation under control. “In Autumn 2023, there were more than 400 asylum hotels in use across the UK at a cost of almost £9m per day, and in the months before the election, the asylum backlog soared again as decision-making collapsed, placing the entire asylum system under unprecedented strain,” a spokesman for the department said.

They added there has been a “rapid increase in asylum decision-making and the removal of more than 24,000 people with no right to be in the UK”.

“By restoring order to the system, we will be able to end the use of asylum hotels over time and reduce the overall costs to the taxpayer of asylum accommodation. There are now fewer hotels open than there were before the election,” the spokesman said.

Legal battles

Langsam himself would no doubt defend his legacy. In the 2011 Guardian interview, he sang the praises of the country his parents made their home, and pointed towards what he saw to be his own contributions to British life.

“My father was the most nationalistic person I have ever come across,” Langsam said. “Britain saved his life and gave him a living and he instilled that in me. I am grateful for what this country has given me.”

He explained his “formula” as enabling “extraordinary buildings” to be “enjoyed by ordinary people”.

Spotting an opportunity appears to be his forte. So, too, perhaps does remaining out of the spotlight.

But past legal battles possibly shed a little more light. In a High Court case in 2010, Langsam sought damages for professional negligence against his former solicitors, Beachcroft, who had acted for him in a previous professional negligence claim that he had brought against his former accountants.

In the first case, which he brought against his accountants Hacker Young, Langsam claimed they had negligently failed to advise him he was entitled to be treated as having non-domicile status. The case was settled shortly before trial with a £1m payment to Langsam.

He then brought the second case against the solicitors who acted for him in the first, arguing he should in fact have recovered £3m, not £1m. He lost this time, both at the High Court and also when he challenged the ruling in the Court of Appeal.

“Mr Langsam is a very wealthy man with what can be described as ‘large personality’,” said the judgment in the second High Court case. “He is clearly used to getting his way and dominating those around him.”

The Court of Appeal judgment described him as “an astute businessman”.